There is something quite special about the Fast, which makes it always solely for God. This specialness comes from God, but is realized through us. There is indeed a connection between fasting, presence (hudur), and contemplative mindfulness (fikr). One could say that fasting as abstaining, deepens our sense of simply or purely being with God, emptied (or emptying) as we are of ourselves, our appetites, our desires, our extraneous thoughts, even our energies to act out certain tendencies, even obsessions. Fasting is a kind of meditation for the body, just as meditation is a kind of fasting of the mind.

One of the great subtleties of fasting is that, as God states through a Tradition of the Prophet (s): “Fasting is indeed for Me, and I shall reward it.” Out of all virtuous and religious acts of obedience, fasting is singled out by God as purely for Him, by the very form and essence of the fast. This is in distinction to other forms or acts of devotion or obligatory worship, which have a human element to them. There is an element of human volition, even self-interest (albeit good and virtuous), that is inextricably linked to all forms or modes of revealed worship, except for the fast, as far God is concerned. According to God, the form of the fast somehow directly reveals its essence, or essential intention, of sincerity.

In fact, every form of meditation or invocation, as well as every other act of obligatory and devotional worship, is sharpened and made more sincere and vigilant by fasting. Fasting is to presence what faqr (poverty/emptiness of soul) is to dhikr (remembrance of God). As a Sufi shaykh once stated so beautifully: “There is no dhikr without faqr, and no faqr without dhikr.” Emptying and awakening. “In your absence is your presence.” Fasting, according to Imam Al-Ghazali, is in essence a non-act. A negative act. An abstention. In other words we actually do nothing while fasting, apart from our intention to abstain for God’s sake (li-wajh Allah) from food, drink, and physical desire. Wajh Allah, literally translated as the Face of God, is another synonym for Presence, as the Presence of God. Therefore, fasting connects us directly to a sincerity of intention for the sake of God’s Presence in the context of our absence, our abstention.

As an abstention or non-act, fasting is a not-doing for God’s sake. By not doing, we emphasize the simplicity of our pure being. A contemplative awareness of simply being is what the non-act of fasting procures. This is fasting’s most precious quality: to return our doing back to simply being: a kind of being present for God by and as our existence. When we are simply present and are purely being for God, we realize that true sincerity involves intimately connecting with God as the very nourishing and unshakable Ground of our Being. It is in this way that through fasting we witness and “taste,” by direct experience (dhawq), a little something of God’s Attribute(s) of Independent Sovereignty (Sammadiya/Qayyumiya). Our hunger, thirst, and fatigue comes and goes, but our conscious awareness and spiritual presence remain, independent of and beyond our bodily needs.

This is why as a non-act, fasting belongs solely to God, who accepts the fast of the servant who fasts by the very virtue of the intent of fasting. In this sense, the intention of the fast is met immediately by the formless act of the fast. Fasting empties us of the impurities of ourselves: impurities which are ultimately linked to a sense of separateness from our true nourishing Source. It leaves us experiencing a sense of lightness with our bodies, and transparency of things, as concerns our contemplative and spiritual seeing of God in all things through the eye of the heart. Fasting disciplines the soul (nafs), weakens our carnal appetites (shahawat), lessens our attachment to the world, and decreases the influence of the devil (especially our inner demons) upon us. Fasting also illumines the heart by emptying or purifying it of our egoic tendencies and awakening it to its own natural disposition (fitra) to know God directly and intimately.

All this is to say that fasting enhances our sense of presence with God and our awareness of God’s Presence with us. By facilitating a holy emptying for God’s sake of that which is other than God in our hearts, our inner heart (fu’ad/sirr) becomes more sensitive and transparent before the presence of God’s Light shining upon the heart (qalb). Fasting awakens our heart to God’s already-present presence that was somehow eclipsed by what we consciously and unconsciously filled our hearts with through our negligence (ghaflah) and over-indulgence.

If we wish to take our fast a bit deeper, we could try the following contemplative practice while fasting. When hunger pangs arise, allow the sensing (or awareness of the sensations) of hunger and bodily fatigue (which come and go) to be a support for your attentiveness to God’s Presence that is always present, reinforcing, as it were, the intention to fast for God’s sake. Allow this kind of mindful sensing and spiritual attentiveness to God (muraqaba) to influence all your daily work: all your activities with your bodily limbs, including your five senses, your extremities, your stomach, and your spiritual heart. Try to feel God’s Presence permeate your body with a sense of lightness and sense of transparency of your experience of the world, as discovered through fasting. It is in this way that fasting can be a beautiful practice of presence with God.

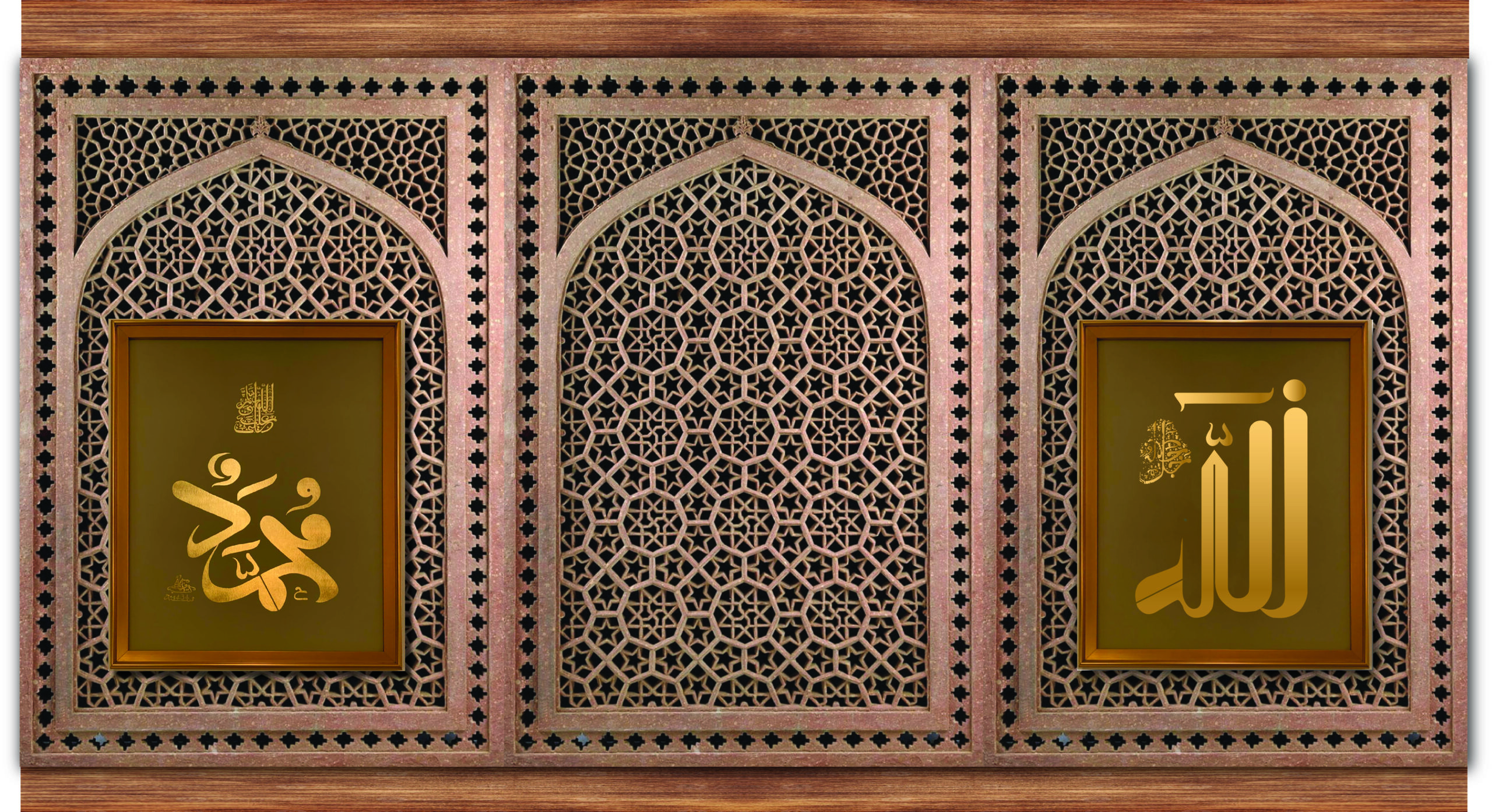

It’s important to note that all of the above concerning fasting is enhanced by the fast of Ramadan, as there is no better fast than the fast of Ramadan with its effects to procure the above. This is realized by both our day-to-day consistency and routine of fasting and ultimately by the grace of God, all of which could be termed the Muhammadan Presence of Ramadan. Ramadan Mubarak!!